The Monroe Doctrine is a long-standing foreign policy principle of the United States that opposes foreign interference in the Western Hemisphere. At its core, it asserts that any attempt by external powers to influence or control countries in North or South America would be viewed as a hostile act against the United States. Though announced in the 19th century, the doctrine has continued to shape U.S. foreign policy well into the 21st century, often in changing and contested forms.

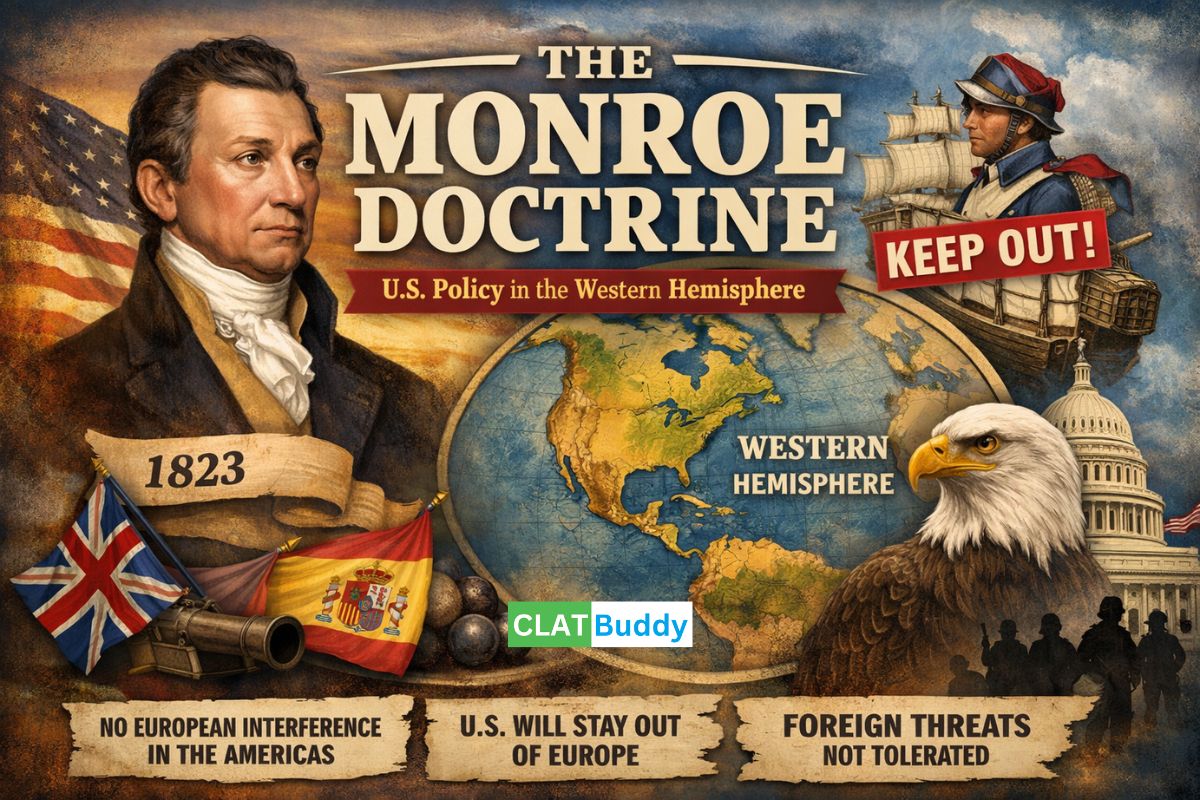

The Monroe Doctrine is a U.S. policy position that draws a clear line between the Americas and the Old World (Europe). It holds that European powers should not interfere in the political affairs of countries in the Western Hemisphere. In return, the United States pledged that it would not interfere in the internal affairs of European nations or their existing colonies.

In simple terms, the doctrine aimed to keep Europe out of the Americas while promising U.S. restraint in Europe.

The doctrine was first articulated on 2 December 1823 by President James Monroe in his seventh annual State of the Union Address to the U.S. Congress. At that time, many Latin American countries were gaining independence from Spanish colonial rule. There were fears that European powers might attempt to re-establish control over these newly independent states.

Monroe declared that:

Interestingly, the policy was not called the “Monroe Doctrine” until 1850, several decades after its announcement.

Although the doctrine sounded assertive, the United States in 1823 lacked a strong navy or army to enforce it. As a result, European colonial powers largely ignored the declaration. In practice, it was the United Kingdom, through its dominant naval power and its policy of Pax Britannica, that indirectly supported the doctrine by discouraging other European nations from intervening in the Americas.

Despite weak enforcement initially, the doctrine laid down an important ideological foundation for future U.S. foreign policy.

Throughout the 19th century, the Monroe Doctrine was violated several times. A notable example was the Second French Intervention in Mexico (1861–1867), when France installed a puppet emperor despite U.S. opposition.

By the early 20th century, however, the United States had emerged as a global power capable of enforcing the doctrine itself. It was increasingly used to justify U.S. involvement and influence in Latin America. During this period, the doctrine became a central element of American grand strategy.

Presidents such as Theodore Roosevelt expanded its scope. The Roosevelt Corollary argued that the U.S. had the right to intervene in Latin American countries to maintain stability, a move that drew criticism for promoting American imperialism.

After 1898, especially following the Spanish-American War, legal scholars and policymakers began reinterpreting the Monroe Doctrine. Instead of unilateral U.S. intervention, it was increasingly framed as supporting multilateralism and non-intervention.

A major shift occurred in 1933 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who promoted the Good Neighbour Policy. The United States formally moved away from military intervention in Latin America and reaffirmed respect for sovereignty. This approach was reinforced through the co-founding of the Organization of American States (OAS), which sought regional cooperation rather than dominance.

In the 21st century, the Monroe Doctrine remains controversial and inconsistently applied. Some leaders have criticised it as outdated or imperialistic, while others have attempted to revive or reinterpret it.

In recent years, especially during the 2020s, the doctrine has been substantially reinterpreted under Donald Trump, particularly in relation to foreign influence in Latin America by countries such as China and Russia. These developments have brought renewed attention to the doctrine’s relevance in modern geopolitics.

The Monroe Doctrine began as a defensive statement against European colonialism but evolved into one of the most influential and debated principles of U.S. foreign policy. Over nearly two centuries, it has been ignored, enforced, expanded, softened, and reinterpreted. Whether viewed as a shield for regional independence or a tool of U.S. dominance, the doctrine continues to influence how the United States engages with the Western Hemisphere.